Chapter 2. Using the stylesheets

In principle, the stylesheets will run with any conformant XSLT 3.0 processor. For many users, that means Saxon. Although earlier versions may work, Saxon 10.1 or later is recommended.

In principle, the instructions for using the stylesheets are

straightforward: using your XSLT 3.0 processor of choice, transform your

DocBook source documents with the docbook.xsl

stylesheet in the xslt

directory of the distribution.

In practice, for most users, running the stylesheets will require getting a Java environment configured appropriately. For many, one of the most significant challenges is getting all of the dependencies sorted out. Modern software development, for better or worse, often consists of one library relying on another which relies on another, etc.

The DocBook xslTNG stylesheets attempt to

simplify this process, especially for the “out of the box” experience

by providing two convenience methods for running the stylesheets: a

jar file with a Main class, and a Python script

that attempts, among other things, to make sure all of the

dependencies are available.

If you’re an experience Java user, you may prefer to simply run the stylesheets directly with Java.

Irrespective of which method you choose, running the stylesheets

is simply a matter of processing your input document

myfile.xml

with

. For example:

xslt/docbook.xsl

|$ saxon myfile.xml -xsl:xslt/docbook.xsl -o:myfile.html

The exact path to docbook.xsl will vary, of course,

but it’s in the xslt directory of the

distribution.

The resulting HTML document contains references to CSS stylesheets

and possibly JavaScript libraries. The output won’t look as nice in your browser

if those resources aren’t available. They’re in the resources directory of the distribution. A quick and easy way to see the

results is simply to send the output to the samples

directory from the distribution. The resources have already been copied into

that directory. In the longer run, you’ll want to make sure that they get

copied into the output directory for each of your projects.

Alternatively, you can copy them to a web location of your choosing and point to them there. You can even point to them in the DocBook CDN, but beware that those are not immutable. The “current” version will change with every release and versioned releases will not persist indefinitely.

Change the $resource-base-uri to adjust the paths

used in the output document.

Many aspects of the transformation can be controlled simply by setting parameters (see I. Parameter reference). It’s also possible to change the transformation by writing your own customization layer (see Chapter 3, Customizing the stylesheets).

2.1. Using the Jar

The ZIP distribution includes a

JAR file that you can run directly. That

JAR file is

$ROOT/libs/docbook-xslTNG-version.jar

where “$ROOT” is whatever directory you chose

to unzip the distribution into and version is the

stylesheet version.

Assuming you unzipped the version 2.4.1-SNAPSHOT distribution into

/home/ndw/xsltng, you can run

the JAR like this:

java -jar /home/ndw/xsltng/libs/docbook-xslTNG-2.4.1-SNAPSHOT.jar

Let’s try it out. Open a shell window and change to the samples directory,

/home/ndw/xsltng/samples assuming you unzipped

it as described above. Now run the java command:

|$|java -jar ../libs/docbook-xslTNG-2.4.1-SNAPSHOT.jar article.xml|<!DOCTYPE html><html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">|…more HTML here...<nav class="bottom"></nav></body></html>

That big splash of HTML was your first DocBook document formatted by the stylesheets! Slightly more usefully, you can save that HTML in a file:

|$|java -jar ../libs/docbook-xslTNG-2.4.1-SNAPSHOT.jar article.xml \-o:article.html

If you now open article.html in your

favorite web browser, you’ll see the transformed sample document

which should look like Figure 2.1, “The sample document: article.xml”.

This is a rendering of the sample document. It consists of the title “Sample Article” centered on the screen with a short paragraph of text below it. The text reads: This is a very simple DocBook document. It serves as a kind of "smoke test" to demonstrate that the stylesheets are working.

The JAR file, run this way, accepts the same command line options as Saxon, with a few caveats:

- No

-x,-y, or-roptions The executable in the JAR file automatically configures Saxon to use a catalog-based resolver and points the resolver at a catalog that includes the files in the distribution.

- No

-initoption The DocBook xslTNG extension functions will be registered automatically.

- Multiple

-catalogoptions You can repeat the

-catalogoption. All of the catalogs you specify will be searched before the default catalog.- Default stylesheet

If you do not specify a stylesheet with the

-xsloption, thexslt/docbook.xslstylesheet will be used automatically.

2.2. Using the Python script

The ZIP distribution includes a

Python script in the bin directory.

This helper script is a convenience wrapper around Saxon. It sets up

the Java classpath and automatically configures a catalog resolver and

the DocBook extension functions.

The script requires the click and pygments packages, which you must install with pip before running the script. For example:

|python3 -m pip install pygments=2.6.1 click

This script behaves much like the JAR file described in Section 2.1, “Using the Jar”. In particular, it accepts the same command line options as Saxon, with the same caveats.

The significant feature of the Python script is that it will attempt to sort out the dependencies for you. It assumes that you’ve used Maven to install the package and its dependencies, so you’ll have to have installed Maven. How you do that varies by platform, but your package manager probably has it.

The following command will assure that you’ve downloaded all of the necessary dependencies. You only have to do this once.

|$|mvn org.apache.maven.plugins:maven-dependency-plugin:2.4:get \-Dartifact=org.docbook:docbook-xslTNG:2.4.1-SNAPSHOT

That might take a while.

The script will work through the dependencies that you have installed, and the things that they depend on, and construct a Java class path that includes them all.

The script stores its configuration in

.docbook-xsltng.json in your home directory.

Options passed to the script are processed as follows: the initial options, all introduced by two hyphens, are interpreted by this script; all the remaining options are passed directly to Saxon.

The script options are:

--helpPrints a usage message.

--config:filenameUse filename as the configuration file. The default configuration file is

.docbook-xsltng.jsonin your home directory.--resources:dirThis option will copy the resources directory (the CSS and JavaScript files) from the distribution into the directory where your output files are going, dir. If dir is not specified, the script attempts to work out the directory from the

-ooption provided to Saxon. If no directory is specified and it can’t work out what the directory is, it does nothing.--java:javaexecUse javaexec as the Java executable. The default java executable is the first one on your

PATH.--home:dirUse dir as the DocBook xslTNG home directory. This should be the location where you unzipped the distribution. (You probably shouldn’t change this.)

--verboseEnables verbose mode; it prints more messages about what it finds.

--debugEnables debug mode. Instead of running the transformation, it will print out the command that would have been run.

--Immediately stop interpreting options. Everything that follows this option will be passed to Saxon, even if it begins with two hyphens.

2.3. Run with Java

Assuming you’ve organized your class path so that all of the dependencies are available (you may find that using a tool like Gradle or Maven simplifies this process), simply run the Saxon class.

For Saxon HE, the class is net.sf.saxon.Transform.

For Saxon PE and EE, the class is com.saxonica.Transform.

2.4. Run with Docker

This is experimental.

The docker directory

contains an experimental Dockerfile. Using docker allows you to

isolate the environment necessary to run the DocBook xslTNG

Stylesheets from your local environment. (If you’re using Linux, see

Section 2.4.1, “Docker on Linux”.)

Using Docker is a three step process. Step 0, you have to have installed Docker!

Build the docker image. In the

dockerdirectory, run the docker build command:|$docker build -t docbook-xsltng .The “

-t” option provides a tag for the image; you can make this anything you want. There’s aVERSIONbuild argument if you want to build a particular release. For example,|$docker build --build-arg VERSION=2.4.1-SNAPSHOT -t docbook-xsltng .will build a Docker image for the 2.4.1-SNAPSHOT release of the stylesheets irrespective of the version in the Dockerfile.

Run the image, for example:

|$docker run docbook-xsltng samples/article.xmlIf you chose a different tag when you built the image, use that tag in place of

in thedocbook-xsltngruncommand. Everything after the container tag becomes options to thedocbookPython script.

The context the script runs in is inside

the container. It can’t for example, see your local filesystem. The

example above works because the distribution is unpacked inside the

container. So the article.xml document isn’t the

one on your local filesystem.

You can use the Docker facilities for mounting directories to change what documents the script can access. For example:

|$|docker run -v /tmp:/output -v /path/to/samples:/input \|docbook-xsltng /input/article.xml chunk=index.html \chunk-output-base-uri=/output/

Assuming that the “samples” directory in the distribution is

located at /path/to/samples, this will chunk the

article.xml sample document that the script sees

in /input

(which is where you mounted samples) and it will write the

output to /output (which is where you mounted

/tmp).

When the script finishes, the chunked output will be in

/tmp.

If you choose to use Docker, you don’t have to rebuild the container

everytime a new stylesheet release occurs. You can simply mount the new

xslt directory into the container

like any other directory.

2.4.1. Docker on Linux

When a Docker container running on Linux writes to the local filesystem, for example because you mounted it in a container, any files written by the container will be owned by “root”. This can be quite inconvenient.

If there’s an elegant solution to this problem, I haven’t found it. Some users have reported success using podman, a Docker-compatible, open source alternative that apparently doesn’t exhibit this behavior.

The following approach will work with Docker, but it’s a bit more complicated.

Create a volume, say docbook-output, with the

docker volumecommand.|docker volume create docbook-outputInstead of mounting a directory on the local filesystem in the container, mount the volume.

Run the transformation.

In order to copy the files off the volume, the volume has to be mounted on a running container. You can start one with

docker run, for example:|

docker run —mount source=docbook-output,target=/out \|--name copy-helper -d busyboxy sleep 3600Copy the files out of the container. For a single file,

docker cpwill do the trick:|docker cp copy-helper:/out/filename.html .If there are multiple output files, you can copy them individually, or you can use

docker exec:|

docker exec copy-helper \|/bin/sh -c 'cd /out && tar cf - .' > out.tarThat’ll copy all the files into the

out.tararchive which you can expand wherever you like.When you have the files, you can stop and remove the container with:

|

docker stop copy-helper|docker rm copy-helperYou may want to remove the volume you created as well:

|docker volume rm docbook-outputand recreate it for the next transformation. If you don’t, be aware that the content of the volume will persist. If you resuse the volume for other transformations, the output from the various transformations will be mingled together on the volume.

And, perhaps obviously, if you remove the volume before you copy the files off of it, the files will be lost.

In short: using a Docker container on Linux is somewhat less convenient.

2.5. Run in Oxygen

“Oxygen” is a family of tools for XML authoring and development. The DocBook xslTNG Stylesheets are not currently shipped with Oxygen. To take advantage of the xslTNG stylesheets, you must setup the transformation scenarios yourself.

Download the nosaxon xslTNG release that you want to use in Oxygen (

docbook-xslTNG-nosaxon-version.zip) and unzip it somewhere in your filesystem. (Oxygen includes Saxon EE; the integration will be cleaner if the release you use does not include a different version of Saxon.)Define a transformation scenario with

path/xslt/docbook.xslas the XSLT file (where path is where you unzipped the release in the previous step.In order to use the extension functions defined in Section 2.6, you have to add the

docbook-xslTNG-version.jarlibrary as an Extension and setorg.docbook.xslt.extensionsas the Initializer class in the Advanced Saxon HE/PE/EE XQuery Transformation Options for the transformation scenario.Without this step the basic transformation will work, but extensions like image metadate extraction with

ext:image-metadatawill not be available.Set the stylesheet parameters accordingly in the transformation scenario.

Run the transformation to generate HTML output. You will have to copy the

resources/cssandresources/jsdirectories to the output location in order to get the styling and interactive features.

2.6. Extension functions

The stylesheets are distributed with several extension functions:

ext:cwd()Returns the “current working directory” where the processor is running.

ext:image-properties()Returns basic properties of an image, width and height.

ext:image-metadata()Returns much more comprehensive image properties and understands far more image types than

ext:image-properties(). Requires the metadata-extractor libraries.ext:pygmentize()Runs the external Pygments processor on a verbatim listing to add syntax highlighting.

ext:pygmentize-available()Returns true if the external Pygments processor is available on the current system.

ext:xinclude()Performs XInclude processing. This extension supports the basic XPointer schemes, RFC 5147 fragment identifiers, and search, a scheme that supports searching in text documents.

ext:validate-with-relax-ng()Performs RELAX NG validation.

At the time of this writing, all of these extension functions require

Saxon 10.1 or later.

Make sure that the docbook-xsltng-version.jar

file is on your class path and use the Saxon -init option to

load them:

-init:org.docbook.xsltng.extensions.Register2.6.1. Extension function debugging

When an extension function fails, or produces result other than

what you expect, it can be difficult sometimes to work out what

happened. You can enable debugging messages by setting the the system

property org.docbook.xsltng.verbose.

Setting the property to the value “true” enables

all of the debugging messages. For a more selective approach, set it

to a comma separated list of keyword values.

The following keywords are recognized:

registrationEnables messages related to function registration.

image-propertiesEnables messages related to image properties.

image-errorsEnables messages related to image properties, but only when the function was unable to find the properties or encountered some sort of error condition.

pygmentize-show-commandEnables a message that will show the pygmentize command as it was run.

pygmentize-show-resultsEnables a message that will show the output of the pygmentize command, before it is processed by the function.

pygmentize-errorsEnables messages related to errors encountered attempting to highlight listings with pygmentize.

2.7. “Chunked” output

Transforming

with

myfile.xmldocbook.xsl usually produces a single HTML

document. For large documents, books like this one for example, it’s

sometimes desirable to break the input document into a collection of

web pages. You can achieve this with the

DocBook xslTNG Stylesheets by setting

two parameters:

$chunkThis parameter should be set to the name that you want to use for the first, or top, page of the result. The name

is a common choice.index.html$chunk-output-base-uriThis parameter should be set to the absolute path where you want to use as the base URI for the result documents, for example

/home/ndw/output/guide/.ⓘNoteThe trailing slash is important, this is a URI. If you specify only

/home/ndw/output/guide, the base URI will be taken to be/home/ndw/output/, and the documents won’t have the URIs you expect.This output URI has nothing to do with where your documents are ultimately published and the documents themselves won’t contain any references to it. It simply establishes the root of output. If you’re running your XSLT processor from the command line, it’s likely that the documents will be written to that location. If you’re running an XProc pipeline, it simply controls the URIs that appear on the secondary result port.

Many aspects of chunking can be easily customized. A few of the most relevant parameters and templates are:

$chunk-includeand$chunk-excludeTaken together, these two parameters determine what elements in your source document will be considered “chunks” in the output.

$persistent-tocIf this parameter is true, then a JavaScript “fly-out” table of contents will be available on every page.

$chunk-navThis parameter, discussed more thoroughly in Section 2.7.1, “Keyboard navigation” enables keyboard navigation between chunks.

t:top-navandt:bottom-navThese templates control how the top-of-page and bottom-of-page navigation aids are constructed.

2.8. Presentation mode

Presentation mode implements paged navigation through a document. For presentation mode, a single document is used (rather than chunking) with some JavaScript code providing the user interface.

As the name implies, it’s designed for use in presentations:

It uses generally larger fonts by default and works best for many small pages

Each unit of a document (part, chapter, article, section, etc.) becomes a page.

Presentation mode replaces earlier “slides” and “speaker notes” implementations.

Beyond the paginated navigation, presentation mode has three key features:

- Synchronization

When served with

https(or fromlocalhostwithhttp), presentation mode can use local storage to synchronize display in different browser windows.Add

|

<meta xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"|name="localStorage.key" content="keyName"/>to the

infoof your document.The key name is irrelevant, but is used to coordinate between windows. All documents with the same key name will be synchronized together. *

Synchronized displays are useful for reading speaker notes in one view while presenting the “normal” view to your audience.

- Speaker notes

Speaker notes can be placed on any page. They are not displayed as part of the normal presentation. They can be revealed by selecting notes view (pressing S).

Use the

speaker-notesrole to add speaker notes.- Progressive reveal

Any elements marked with the role

revealwill be hidden initially. Navigating forward or pressing Space will reveal them.When applied to lists, the behavior applies to all of the items except the first.

If an item is marked both

revealandtransitory, it will be revealed in turn and then concealed again when the next item is revealed. This allows one to create the illusion, for example, of bullet items being replaced.

In sort, you get:

Quick and easy presentations from DocBook documents.

No special markup required.

Easy navigation.

Clean look and feel.

Advanced features:

Synchronized display

Speaker notes

Progressive and transitory reveals

Pressing F1 in a presentation mode document will display a summary of the keyboard navigation shortcuts.

There’s a small customization layer in the distribution,

presentation.xsl that enables presentation mode

and changes some of the generated text so that the labels “Part”, “Chapter”, and so forth aren’t

in the output.

2.9. Effectivity attributes and profiling

When documenting computer hardware and software systems, it’s very common to have different documentation sets that overlap signficantly. Documentation for two different models of network router, for example, might differ only in a few specific details. Or a user guide aimed at experts might have a lot in common with the new user guide.

2.9.1. Effectivity

There are many ways to address this problem, but one of the simplest is to identify the “effectivity” of different parts of a document. Effectivity in this context means identifying the parts of a document that are effective for different audiences.

When a document is formatted, the stylesheets can selectively include or omit elements based on their configured effectivity. This “profiled” version of the document is the one that’s explicitly targeted to the audience specified.

DocBook supports a wide variety of common attributes for this purpose:

| Attribute | Nominal effectivity axis |

|---|---|

| arch | The architecture, Intel or AMD |

| audience | The audience, operations or development |

| condition | Any condition (semantically neutral) |

| conformance | The conformance level |

| os | The operating system, Windows or Linux |

| outputformat | The output format, print or online |

| revision | The revision, 3.4 or 4.0. |

| security | The security, secret or top-secret |

| userlevel | The user level, novice or expert |

| vendor | The vendor, Acme or Yoyodyne |

| wordsize | The word size, 32 or 64 bit |

DocBook places no constraints on the values used for effectivity

and the stylesheets don’t either. You’re free to use “cat” and “dog”

as effectivity values in the wordsize attribute, if you

wish. The further you deviate from the nominal meaning, the more

important it is to document your system!

Consider Example 2.1, “A contrived effectivity example”.

<para>This is an utterly contrived example of

some common text. Options are introduced with the

<phrase os="windows">/</phrase>

<phrase os="mac;linux">-</phrase> character.</para>If this document is formatted with the $profile-os

parameter set to “windows”, it will produce:

This is an utterly contrived example of some common text. Options are introduced with the / character.

If “mac” or “linux” is specified, it will produce:

This is an utterly contrived example of some common text. Options are introduced with the - character.

If the document is formatted without any profiling, all of the versions will be included:

This is an utterly contrived example of some common text. Options are introduced with the / - character.

That is unlikely to work well.

2.9.2. Other common Attributes

In addition, the stylesheets support profiling on several common attributes

that are not explicitly for effectivity: xml:lang, revisionflag,

and role.

The stylesheets treat the role attribute as

multi-valued, similar to the class attribute in HTML. It

may contain a sequence of tokens, seperated by whitespace. This allows you, for example,

to classify a section as informal which should be printed in

landscape orientation with the role value

“informal landscape”.

2.9.3. Profiling

The profiling parameters are applied to every document:

$profile-arch,

$profile-audience,

$profile-condition,

$profile-conformance,

$profile-lang,

$profile-os,

$profile-outputformat,

$profile-revision,

$profile-revisionflag,

$profile-role,

$profile-security,

$profile-userlevel,

$profile-vendor, and

$profile-wordsize. Each of these values is treated

as a string and broken into tokens at the

$profile-separator.

For every element in the source document:

If it specifies a value for an effectivity attribute, the value is split into tokens at the

$profile-separator.If the corresponding profile parameter is not empty, then the element is discarded unless at least one of the tokens in the profile parameter list is also in the effectivity list.

In practice, elements that don’t specify effectivity are always included and profile parameters that are empty don’t exclude any elements.

2.9.4. Dynamic profiling

Dynamic profiling is a feature that allows you to profile the output of the stylesheets according to the runtime values of stylesheet parameters. You can, for example, produce different output depending on whether or not chunking is enabled or JavaScript is being used for annotations.

To enable dynamic profiling, set the $dynamic-profiles

parameter to “true”.

In the interest of performance, security, and legibility,

dynamic profiles don’t support arbitrary expressions.

You can use a variable name by itself, $flag, which tests

if that variable is true, or you can use a

simple comparison, $var=value which tests if (the string value of)

$var has the value value.

(If $var is a list, it’s an existential

test.) You also can’t use boolean operators or any other fancy expressions.

If you really need to have a dynamic profile based on some arbitrary condition, you can do it by making a customization layer that stores that computation in a variable and then testing that variable in your dynamic profile.

An element with dynamic profiling will be published if none of it’s profile expressions evaluate to false. This is slightly different from the ordinary profiling semantic which publishes the element if any of it’s values match.

2.10. Customize individual cross references

Most kinds of generated text apply across an entire document: do you want chapters to be numbered? Should generated text be in English or French? What form should numbered and unnumbered sections have? The mechanisms for changing this generated text are described in Chapter 4, Localization. These mechanisms control the formatting of cross references.

But it’s sometimes useful to be able to change the format of a cross reference on an individual basis (that is, on the basis of the context in which the reference occurs, not the nature of what is referenced). You might, for example, want to shorten a cross reference to just a label if it’s already been referenced several times.

Consider a cross reference to a section:

see <xref linkend="syntax-highlighting"/>.

In the localization style of this guide, that is rendered like this:

see Section 2.11, “Syntax highlighting”.

The text that is generated by a cross reference can be customized

for individual references with the xrefstyle attribute.

For example,

see <xref linkend="syntax-highlighting" xrefstyle="%l"/>,

will produce a result like this:

see 2.11.

You can use the %c, %l and

%p values from Table 4.1, “Template %-letter substitutions” in

xrefstyle. There is also an additional

%label for the full Label, which is

the component`s name and number. The use of these percent-values is

explained in the following table. The result column shows how a

cross references to the section below entitled

Syntax highlighting would appear

in each xrefstyle.

Value of xrefstyle attribute on xref | Result | Remark |

|---|---|---|

(@xrefstyle is absent) | Section 2.11, “Syntax highlighting” | Default |

%c | Syntax highlighting | Content, e. g. title of target |

%l | 2.11 | Label, usually the target’s number. |

%label | Section 2.11 | The full Label, usually the target’s number and name. |

%p | Page number in print output (PDF). Displays as “#” in HTML. | |

%label (%c) | Section 2.11 (Syntax highlighting) | You can combine %-letters with text |

Legacy values for xrefstyle

In order to support migration from XSLT 1.0 Stylesheets, xslTNG supports the

template: Syntax which is explained in

“Customizing

with an xrefstyle attribute / Using template:” in

the book “DocBook XSL: The Complete

Guide”. This is summarized in the following

table.

Value of xrefstyle attribute on xref | Result | Remark |

|---|---|---|

template:the chapter numbered %n | the chapter numbered 2.11 | XSLT 1.0 Legacy Syntax |

template:the chapter called %t | the chapter called Syntax highlighting | XSLT 1.0 Legacy Syntax |

Using pagenumber in cross-references

The %p value in xrefstyle makes

little sense in HTML output, since there are no page numbers. If you use it

anyway, it will be displayed as

“”.

This may be confusing for readers. A possible solution for this problem is the use of

the outputformat attribute. For example:

The

outputformatattribute was intoduced in Section 2.9, “Effectivity attributes and profiling” and Table 2.1.

The paragraph markup in that example is:

1 |<para>The <code>outputformat</code> attribute was intoduced in|<xref linkend="profiling"/> and|<xref linkend="table.effectivity-attributes" xrefstyle="%label"|/><phrase outputformat="print"> on page5 |<xref linkend="table.effectivity-attributes" xrefstyle="%p"|/></phrase>.|</para>

Where the page number appears in the print version, but not in the HTML version. Note that some care has been taken with line breaks and spaces around markup to avoid extraneous whitespace in either version.

2.11. Syntax highlighting

Program listings and other verbatim environments can be “syntax highlighted”, that is, the significant tokens in the listing can be colored differently (keywords in red, quoted strings in blue, that sort of thing).

The default syntax highlighter is Pygments, an external Python program. This has the advantage that the highlighted listing is available to the stylesheets. The stylesheets can then render line numbers, call outs, and other features.

But running an external program for every verbatim environment requires having the external program and also, if there are many verbatim environments, may slow down the formatting process

An alternative is to use a JavaScript highlighter in the browser such as highlight.js or Prism. This approach has no impact on formatting and doesn’t require an external process. However, it means the xslTNG Stylesheets have no control over the process. Most of the verbatim options only apply when Pygments is used.

The choice of syntax highlighter is determined by the

$verbatim-syntax-highlighter parameter.

2.12. Persistent table of contents

The persistent Table of Contents (ToC) provides a full ToC for an entire document accessible from each chunked page.

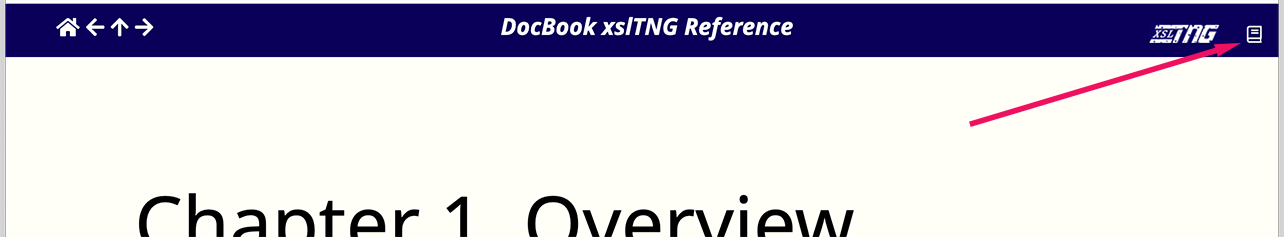

The ToC is accessed by clicking on the “book” icon in the upper right corner of the page as shown in Figure 2.2, “Opening the ToC”.

The icon and other aspects of the style can be changed by providing

$persistent-toc-css.

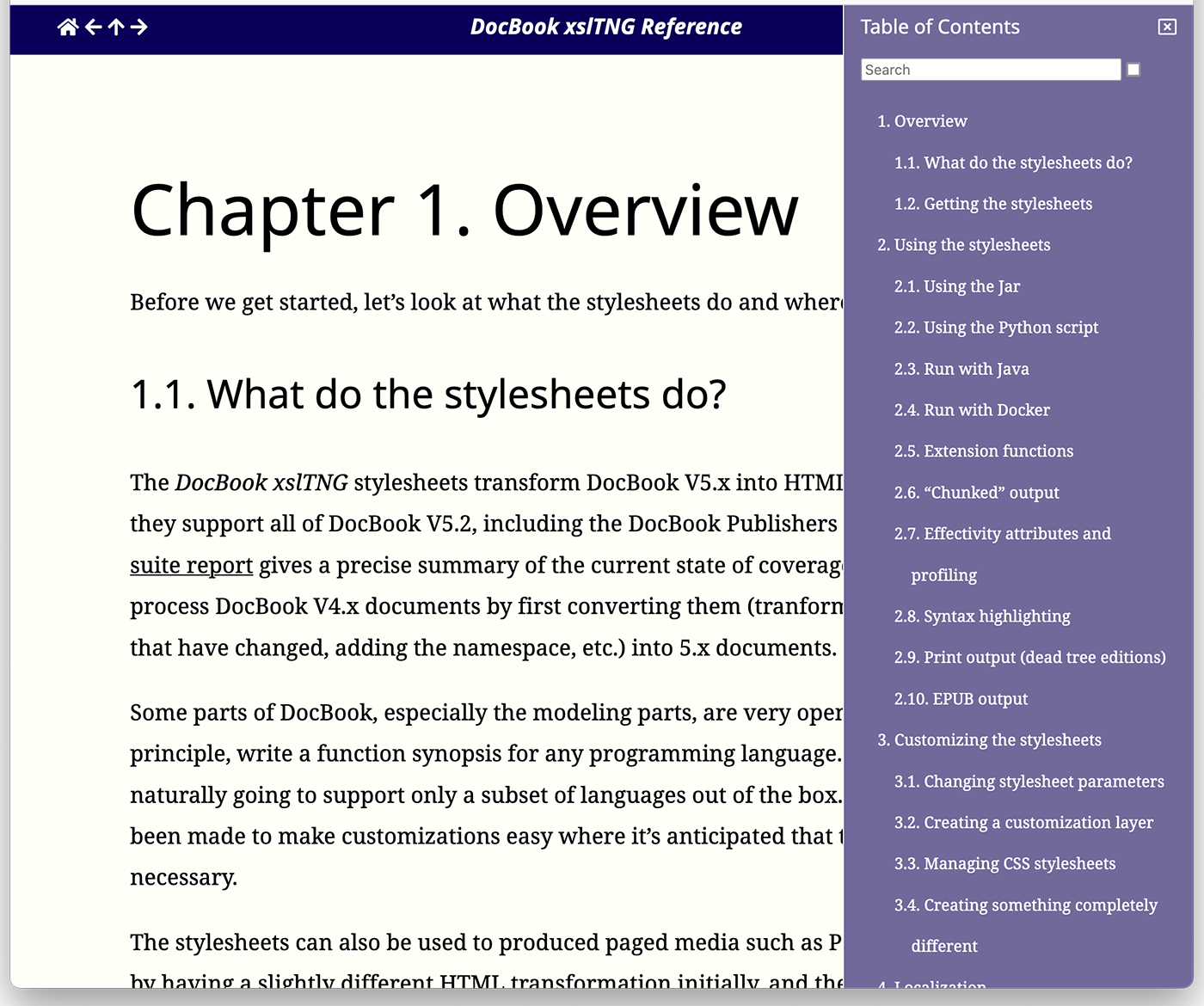

Once open, the ToC is displayed. A long ToC will be scrolled to the location of the current page in the document as shown in Figure 2.3, “The Persistent ToC”.

The persistent ToC popup is transient by default, meaning that

it will disappear if you use it to navigate to a different page. If

you open the popup by “shift-clicking” on it, the ToC will persist

until you dismiss it. This can also be accomplished by selecting the

check box in the ToC. The presense of the search bar is controlled by

the $persistent-toc-search parameter.

2.12.1. Persistent ToC data

The data used by the persistent ToC can be stored in a separate

file or stored in each chunk. This is controlled by the

$persistent-toc-filename.

If chunking is enabled and the

$persistent-toc-filenameparameter is non-empty, it’s used as a filename and a single copy of the ToC will be saved in that file.The benefit of this approach is that the HTML chunks are smaller. If the persistent ToC is written into every chunk, the size of each HTML chunk increases in proportion to the size of the ToC. For a large document with lots of small pages, this can be a significant percentage of the overall size.

There are two disadvantages:

This will not work if the documents are accessed with

file:URIs: you must usehttp(and in some environments, perhapshttps) to load the documents. The browser will (quite reasonably) not allow JavaScript to load documents from the filesystem.Also, with this approach, opening the ToC requires another document to be loaded into the browser. For a large ToC, this can introduce visible latency, although browser caching tends to reduce that after the document has been loaded once.

If the

$persistent-toc-filenameparameter is the empty sequence, a copy of the ToC is stored in each chunk.ⓘNoteWhen stored in each chunk, the Table of Contents is secreted away in a

scriptelement so that it will be ignored by screen readers and other user agents that don’t support JavaScript or CSS.The benefit of this approach is that it requires no additional document to be loaded and will work even if the documents are loaded with

fileURIs.The disadvantage of this approach is that it increases the size of each chunk. Whether that matters depends on the size of the ToC, the relative size of the chunks, bandwidth and other constraints.

If chunking is not being used, there will only be one HTML result and the ToC will always be stored in that chunk.

2.13. On-page table of contents

Documents come in many shapes and sizes. Consequently, there are a variety of navigation mechanisms available. For long documents, such as books, a Table of Contents (ToC) is traditional (as are indexes). For web presentation, long documents may be broken into chunks, for example at the chapter level. In this case, header and footer navigation between chunks is almost always available. For large documents a “persistent ToC” can enable quick navigation from any chunk.

You can also enable an on-page ToC. The on-page ToC provides a navigation mechanism for sections within a page. By default, it appears on the right of the page if the window is wide enough to comfortably display it next to the main body.

The current implementation requires JavaScript. In fact it is not

constructed from the DocBook markup, but instead from the HTML markup when

the page is rendered. To be precise, the ToC is constructed from HTML

section elements that

begin with a header that

contains an

h1…h6

element. It is therefore either a bug or a feature, depending on your perspective,

that a customization layer that changes how sections are marked up will change

what appears in the ToC. If you simply wish to suppress a particular section

from appearing in the ToC, add nopagetoc to its

class attribute.

Several parameters control presentation and formatting of the on-page ToC.

$pagetoc-elementsA list of the names of the elements (technically, the classes of the sections) that should get an on-page ToC. It’s empty by default (meaning no such ToC is rendered). For the standard presentation of this guide, the list is set to

preface chapter appendix refentry. (The sneaky among you may wonder if you could simply set it to “component” because that class is used for all those elements; “Yes. Yes, you could.”)$pagetoc-dynamicDetermines whether or not the ToC is “dynamic”. Inspired by Kevin Drum’s table of contents progress animation, the ToC keeps track of the reader’s location in the main view and highlights the corresponding sections in the ToC (albeit without the clever SVG animation of the original).

Set this parameter to false if you find the animation distracting. (If the animation is enabled, a control is provided to let the reader turn it off, in case they find it distracting.)

$pagetoc-jsThis is the JavaScript that implements the on-page ToC. Changing this parameter allows you to replace it with JavaScript of your own invention.

- CSS

There is no

pagetoc-cssparameter; the CSS is integrated into the standard CSS. You can find it in thepagetoc.scssfile in the repository if you want to change the presentation. (Don’t change that file, simply add overriding rules later in the cascade.)

There is also a JavaScript API that you can use to control some features

of the presentation. This is done by adding a DocBook property to

the browser’s window object. The value of the DocBook property

should be a map. To control the on-page ToC, add a pagetoc property

to the DocBook map. The value of this property must also be a map.

The properties of the pagetoc map can be used to change

the display:

decoratedThis is the markup used for the user-control on the on-page ToC when the ToC is decorated. The default value is “

☀”.plainThis is the markup used for the user-control on the on-page ToC when the ToC is plain (not decorated). The default value is “

○”.hiddenThis is the markup used for the user-control on the on-page ToC when the ToC is hidden. The default value is “

◄”.nothing_to_revealThis property controls how the on-page ToC is rendered if there are no additional sections to be revealed. It can have the value “

hide”, to hide the ToC, “plain” to make its presentation plain in this case, or “decorated” to use the decorated style. The ToC will not appear if there are no sections.

To use the JavaScript API, make sure your assignments to the

DocBook object are performed before the

on-page ToC JavaScript is executed.

2.14. Paged-media (print output)

Formatters, the tools that turn markup of any sort into aesthetically pleasing (or even passably acceptable) printed pages are fiendishly difficult to write.

In the XML space, there have been a number of standards and vendor-specific solutions to this problem. The current standards are XSL FO and CSS.

At present, the DocBook xslTNG Stylesheets are focused on CSS for print output. There’s a customization layer that produces “paged-media-ready” HTML that can be processed with a CSS formatter such as Antenna House or Prince.

To get print output, format your documents with the

print.xsl stylesheet instead of the

docbook.xsl stylesheet. The additional cleanup provided

by print.xsl assures that footnotes, annotations, and

other elements will appear in the right place, and with reasonable

presentation, in the printed version.

The resulting HTML document can be formatted directly with a CSS paged-media formatter.

2.14.1. Landscape orientation

The default orientation for pages in print output is portrait. The stylesheets support a simple mechanism for selecting landscape pages. This works in many common cases, but you may need additional CSS if you have complex requirements.

This feature enables whole pages with a landscape orientation. It doesn’t support rotating a single block element (paragraph, table, figure, etc.) to lanscape orientation within an otherwise portrait page. If you rotate a single block element, it will introduce a page break before and after the element.

Rotations within an otherwise portrait page might be possible with custom CSS, depending on your formatting engine.

The stylesheets slightly abuse the role attribute

(which is multi-valued) for this

purpose. Placing the token landscape in the role attribute

will select lanscape orientation for the element on which the role

attribute appears. (Placing the token portrait in the role

attribute will select portrait orientation in an otherwise landscape document.)

This may apply to the whole book or

article, or to individual chapter, section or

appendix elements.

You can also print individual tables or figures in landscape, if they are

too wide for portrait pages. For wide tables, you should use the

orient attribute with the value land, because it is

provided precisely for this purpose. However, in the interests of a uniform

solution, the role attribute with the value landscape

can also be used for tables.

For legacy reasons, the landscapeFigure processing instruction from the XSLT 1.0 stylesheets is also supported for figure and

informalfigure elements, as described

in Chapter 18 of Bob Staytons Complete Guide

.

2.14.1.1. AntennaHouse extensions

The rotation mechanism supported by standard CSS rotates the entire page, including any running headers and footers. For documents that are read online, this has some real advantages as the PDF viewer is likely to show the landscape pages “the right way up”.

But for documents that are going to be printed, or where a more traditional presentation is desirable, the goal is usually to rotate the content of the page, but not the page itself.

This can be accomplished with the AntennaHouse formatter using the

$vendor-css extension. In an otherwise portrait document,

including the vendor-ahf-portrait.css file using

$vendor-css will present landscape rotations in the

portrait page. If the document is being printed on landscape pages,

including the vendor-ahf-landscape.css file using

$vendor-css will present portrait

rotations in the landscape page.

2.15. EPUB output

The DocBook xslTNG Stylesheets will

produce output designed for EPUB(3) if you use the

epub.xsl stylesheet instead of

docbook.xsl. This is new in version 1.11.0 and

may be incomplete. The output conforms to

EPUBCheck

version 3.2.

Producing an EPUB file is a slightly complicated process. You must produce (X)HTML that conforms to strict requirements, you must produce a media type document containing a specific text string, you must produce a manifest that identifies all of the content including all the images, stylesheets, fonts, etc, and you must finally create a ZIP archive (with some special consideration as well).

The stylesheets can only do part of this process. In some future release where we use, for example, an XProc 3.0 pipeline, it may be practical to do more.

When you run the EPUB stylesheet, the principle result document is the media type document. This has two useful side effects: first, it establishes the output base URI from which all the relative documents can be created, and second, if you fail to process some element in the input, you’re likely to get extra text characters in the principle result document. That will cause tools to reject the EPUB and draw your attention to the error.

The stylesheets also produce the META-INF files and the OPS directory containing the document parts and the manifest.

There are two parameters specific to EPUB:

pub-idThis is the unique identifier for your EPUB. If you don’t specify one, a random one will be generated for you.

manifest-extraThis is a URI. If it’s specified, then it must be an XML document and that will be added to the EPUB manifest. This is how you can add links to media and other resources that the stylesheets don’t know about.

2.15.1. Adding metadata

You can add elements to the info element of the root element of your

document to add metadata to your EPUB files. Elements in the Dublin Core namespace

will be copied through. You can also add the elements

meta and link in the special namespace

http://docbook.org/ns/docbook/epub.

2.15.2. EPUB in action

The Getting Started project has been updated to show how to create EPUB from a book. The project has support for dealing with external media, fonts, and constructing the final ZIP file.

2.16. Ad hoc CSS styling

Generally speaking, it’s considered good practice to separate content from presentation. On the web, this is most often accomplished with clean, structural HTML as the content and CSS styling providing the presentation. Indeed, that’s how the output from the DocBook xslTNG Stylesheets is structured.

And yet, sometimes you need to tweak individual elements in

small ways. For example, you may want to change the style of a single

programlisting to avoid a page break inside it. Or perhaps

you need to make some adjustment to a single image.

In principle, this can be done in a completely “hands off” manner: add an ID to the element and add an ID selector to the external CSS file. In practice, that’s a bit tedious and there’s nothing in the source to suggest that the styling is required or even exists.

HTML allows for inline styles with the style attribute and starting in version 2.1.5,

the xslTNG stylesheets provide a way to access this feature.

DocBook allows namespace qualified attributes on any element.

Adding attributes in the https://xsltng.docbook.org/ns/css

namespace to an element will add those properties to the HTML style attribute. For example:

|<para xmlns:css="https://xsltng.docbook.org/ns/css"

| css:border="1px solid blue" css:border-radius="0.5em"

| css:padding="0.5em">This

|is a paragraph with a border.</para>

Will be rendered as you expect:

This is a paragraph with a border.

The generated HTML wraps up the CSS properties in a style attribute:

|<p style="padding:0.5em;border:1px solid blue;border-radius:0.5em;"|>This is a pargraph with a border.</p>

To facilitate different properties based on the output medium, the stylesheets

will also look for attributes in the

“https://xsltng.docbook.org/ns/css#”

namespace. For example, this paragraph:$output-media

1 |<para xmlns:p-css="https://xsltng.docbook.org/ns/css#print"

| xmlns:css="https://xsltng.docbook.org/ns/css"

| css:background-color="#ffaaaa"

| p-css:background-color="#bbbbbb">This paragraph

5 |has a background color.

|</para>

Will be rendered with a pinkish background online and with a grey background in print:

This paragraph has a background color.

By default, the stylesheets set

$output-media to screen for

“ordinary output”, epub for EPUB, and

print for paged media.