Chapter 4. Localization

The DocBook xslTNG stylesheets support localization in more than 70 languages. At the time of this writing: Afrikaans, Albanian, Amharic, Arabic, Assamese, Asturian, Azerbaijani, Bangla, Basque, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Catalan, Chinese, Chinese (Taiwan), Chinese Simplified, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Finnish, French, Galician, Georgian, German, Greek, Gujarati, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indian Bangla, Indonesian, Irish, Italian, Japanese, Kannada, Kirghiz, Korean, Latin, Latvian, Lithuanian, Low German, Malayalam, Marathi, Mongolian, Northern Sami, Norwegian Bokmål, Norwegian Nynorsk, Oriya, Polish, Portuguese, Portuguese (Brazil), Punjabi, Romanian, Russian, Serbian in Cyrillic script, Serbian in Latin script, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Tagalog, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Turkish, Ukrainian, Urdu, Vietnamese, Welsh, and Xhosa.

4.1. Background

Near the end of the previous millennium, I was working on the DSSSL stylesheets for DocBook. They were popular enough that users of languages other than English wanted to use them.

I invented a mechanism for doing simple localization so that the word “Chapter” in “Chapter 5” would, for example, be spelled “Chapitre” if the book was in French, and “Розділ” if it was in Ukrainian. What started as a simple word substitution system grew a few macro facilities and became a little more sophisticated*.

Over time, with the aid of dozens of volunteers around the world who contributed files for their languages, the DocBook stylesheets developed localization capabilities that were for the most part good enough.

Fast forward a few years and those language-specific localization files, and some of those mechanisms, were ported to the XSLT 1.0 stylesheets for DocBook.

Fast forward another decade and those XSLT 1.0 localization files and some of the mechanisms were ported to the XSLT 2.0 stylesheets for DocBook.

Fast forward the better part of another decade and those XSLT 2.0 localization files and some of the mechanisms were ported to the DocBook xslTNG stylesheets.

Well. Sort of. Initially, I tried to replace the complex system of templates with a model that took the text that had to be generated and decomposed it into logical parts. It worked fine for English and many other languages, but didn’t account for the complexity of many others, such as Chinese.**

Starting in version 2.0.0, the xslTNG stylesheets have reverted back to a templating system. The localization files have been transformed a little bit to make some of the customization easier (I hope). They can’t stray too far from the original designs because I must reuse the localization data I have. I don’t want to devise a system that requires another army of volunteers to provide new localization data.

4.1.1. Consequences

One unfortunate consequence of this history is that there’s some cruft in the localization files. There are mappings and possibly templates that aren’t actually used. Or, at least, they’re not used in the standard DocBook stylesheet. They might be used in customization layers.

I made a few attempts to trim out cruft, but found all of the results unsatisfying. So, at least for the moment, I’ve left it in place. Like everything on earth, it’s mostly harmless.

4.2. Overview

In this context, localization mostly refers to “generated text”, words and symbols that appear in a published DocBook document that aren’t present in the original XML. Consider Figure 4.1, “Sample book source”.

1 |<book xmlns="http://docbook.org/ns/docbook"

| version="5.0" xml:lang="en">

|<info>

| <title>Localization Example</title>

5 |</info>

|<part>

|<title>Part the first</title>

|<chapter xml:id="chap">

|<title>Chapter the first</title>

10 |<para>This is a tiny sample chapter.

|See also <xref linkend="app"/>.</para>

|</chapter>

|</part>

|<appendix xml:id="app">

15 |<title>An appendix</title>

|<para>This is a tiny sample appendix.

|See also <xref linkend="chap"/>.</para>

|</appendix>

|</book>

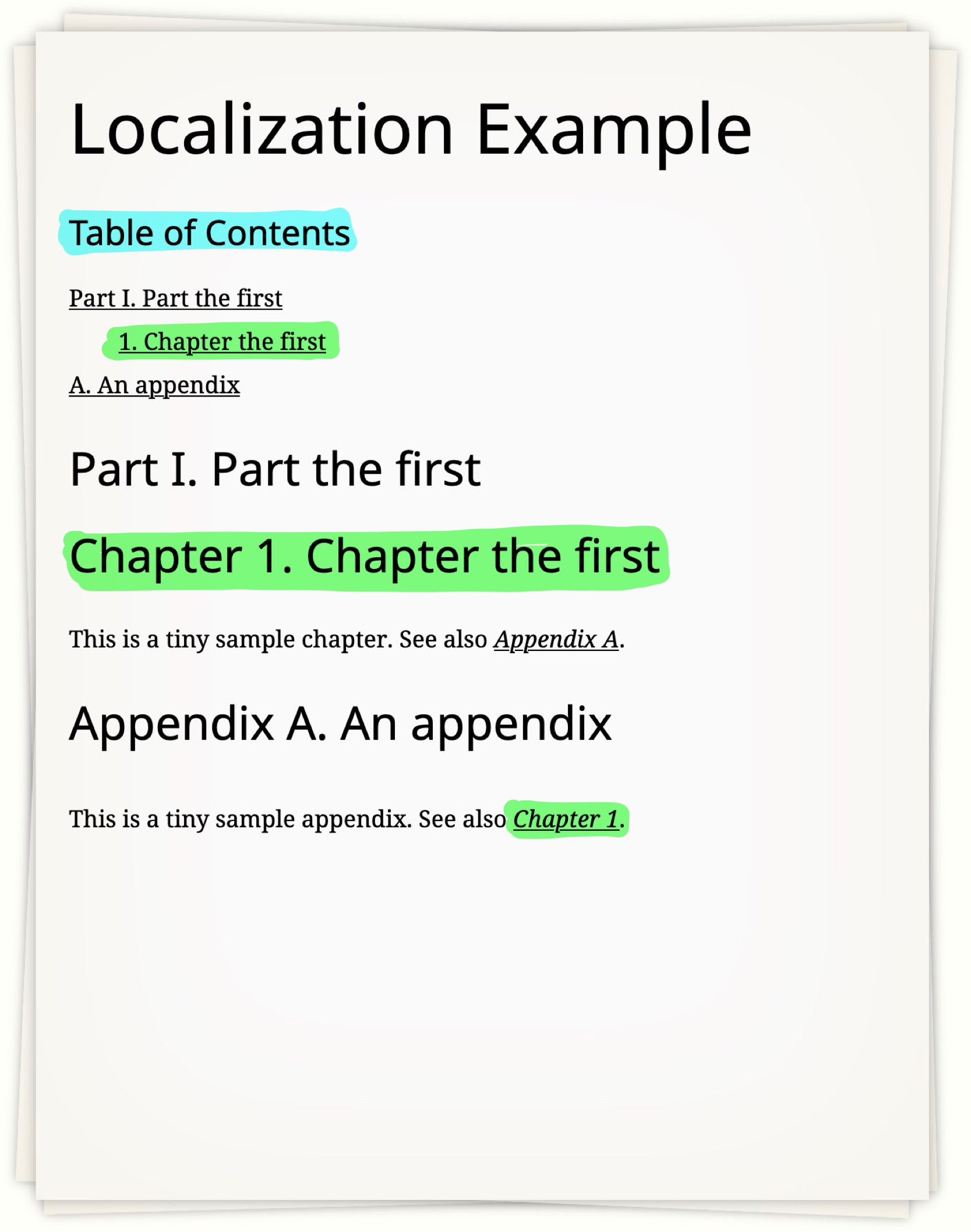

It might be published as shown in Figure 4.2, “Sample book (annotated)”. Here we can see examples of several different kinds of generated text.

The title “Table of Contents” is entirely generated; it appears nowhere in the XML. The chapter title appears in the text, but it’s labeled “1.” in the list of titles, “Chapter 1.” in the chapter itself, and “Chapter 1” (without the title) in the cross reference.

Now consider a French version of the document in Figure 4.3, “Sample book source (French)”.

1 |<book xmlns="http://docbook.org/ns/docbook"

| version="5.0" xml:lang="fr">

|<info>

| <title>Exemple de Localisation</title>

5 |</info>

|<part>

|<title>Première partie</title>

|<chapter xml:id="chap">

|<title>Chapitre un</title>

10 |<para>Ceci est un petit exemple de chapitre.

|Voir aussi <xref linkend="app"/>.</para>

|</chapter>

|</part>

|<appendix xml:id="app">

15 |<title>Annexe</title>

|<para>Ceci est un petit exemple d’annexe.

|Voir aussi <xref linkend="chap"/>.</para>

|</appendix>

|</book>

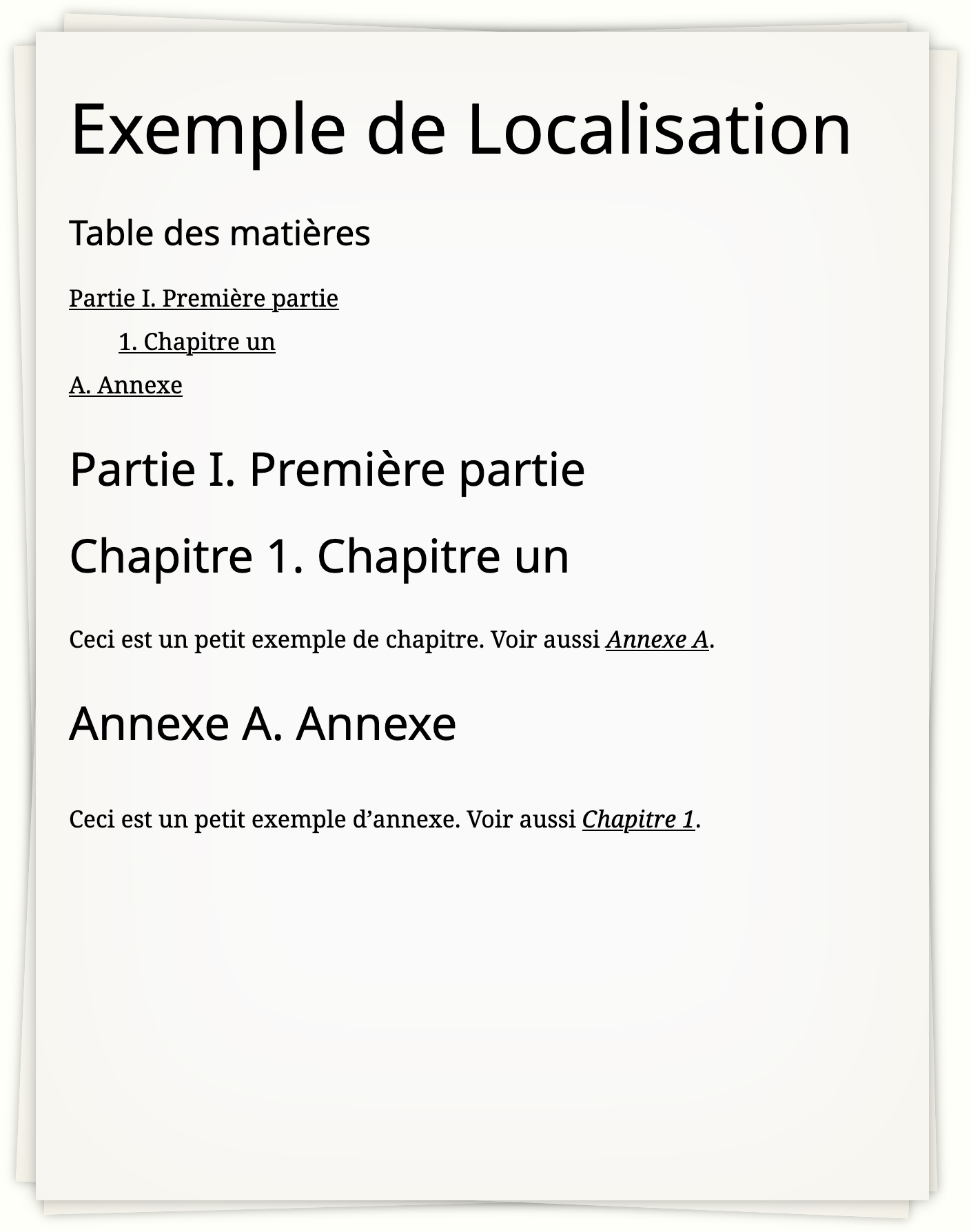

In this case, the published version will have different localization, as shown in Figure 4.4, “Sample book (French)”.

The question is, how is this accomplished? The answer, I’m afraid, is not simple.

It begins with a localization file.

4.3. Localization files

The localization files are in

src/main/locale in the repository. The

localization file is designed to be simple enough to edit by hand. The stylesheets

use compiled versions created by processing the input locale with

src/main/xslt/modules/xform-locale.xsl to produce

the files in

xslt/locale in the distribution.

A locale begins by defining the language it supports and

providing an English language name for it. The language

attribute identifies the language (in the same terms as

xml:lang) to which this localization applies.

That’s followed by metadata about the file (authors, etc.), then mappings, groups, lists, and letters as shown in Figure 4.5, “Example locale file (excerpted)”. We’ll consider each section in detail below.

1 |<locale xmlns="http://docbook.org/ns/docbook/l10n/source"

| xmlns:db="http://docbook.org/ns/docbook"

| language="en" english-language-name="English">

| <info>

5 | …

| </info>

| <mappings>

| <gentext key="above">above</gentext>

| …

10 | </mappings>

| <group name="title">

| <template match="self::db:chapter">{chapter} %l%.%c</template>

| …

| </group>

15 | <list name="_default">

| <items>%c</items>

| <items>%c {and} %c</items>

| <items>%c<repeat>, %c</repeat>, {and} %c</items>

| </list>

20 | <letters>

| …

| </letters>

|</locale>

4.3.1. Mappings

The mappings section is a simple list of key/value pairs.

Each gentext element defines a key and its replacement.

1 | <mappings>

| <gentext key="above">above</gentext>

| <gentext key="abstract">Abstract</gentext>

| …

5 | <gentext key="xrefto">xref to</gentext>

| </mappings>

These mappings serve two purposes. For many languages, a lot of the work of defining a new localization is just updating these mappings. For a stylesheet customization layer, it provides a mechanism for remapping on an ad hoc basis.

In a localization template, any key entered in curly braces will

be replaced by the mapping. In other words, for the example above,

{abstract} will be replaced by the word “Abstract”.

This mapping is done when the document is transformed, not when the

localization file is compiled.

4.3.2. Group

Groups are the primary templating system. In a context where

generated text is required, a group is selected and within that group,

a template is selected. The template is selected by evaluating the

expression in the match attribute with the current node

as the context item. A template with the match express true()

will always succeed; it is used as a fallback.

The title-numbered group determines how

titles are formatted if they are numbered, (there’s also

title-unnumbered when titles aren’t being

numbered):

1 |<group name="title-numbered">

| <template match="self::db:section[ancestor::db:preface]">%c</template>

| …

| <template match="self::db:appendix">{Appendix} %l%.%c</template>

5 | …

| <template match="self::db:warning">%c</template>

| <template match="true()">%l%.%c</template>

|</group>

(Note that not all titles are numbered,

this is just the group that’s used if they could be. See

$division-numbers,

$component-numbers, and

$section-numbers.)

Within a template, two kinds of substitution are performed: names in curly braces are replaced by the corresponding mapping and %-letter values are substituted as follows:

| %-letter | Substitution |

|---|---|

%c | The content (for example, the text of the title) |

%l | The label (for example, “Chapter 1” or “see also”) |

%p | The page number (not yet implemented) |

%o | The olink title (not yet implemented) |

%. | The separator (often, “. ”) |

%% | A literal % character |

If the title group is being used to generate

text for the chapter from our example

document:

The

chaptercontext is used to select the template ({chapter} %l%.%c).The string

{chapter}is replaced by the mapping forchapter, which is “Chapter” in English.The label

%lis “1” because this is the first chapter. (In fact, constructing the label uses templates from the localization file as well.)The separator

%.is “. ”. (Like the label, this is also constructed from a separate query to the localization file.)And the content

%cis “Chapter the first”. (There’s no markup in this title, but if there was, it would be retained. The content is a list of items, not a string.)Literal text, such as the non-breakable space between “

{chapter}” and “%l”, is retained verbatim.

4.3.3. List

List elements are used to format items that can be repeated (terms

in a variable list, lists of authors, lists of “see also” terms, etc.).

The list consists of a series of items. Within each item, one or more

content replacements is specified with %c. The items

must be arranged so that there’s a match for one, two, three, etc. items.

If an item contains a repeat, that repeat will be used for as many items as necessary to complete the list formatting. The default list format is:

1 | <list name="_default">

| <items>%c</items>

| <items>%c {and} %c</items>

| <items>%c<repeat>, %c</repeat>, {and} %c</items>

5 | </list>

Consider how a list of four authors in an authorgroup

would be formatted. Call them A, B, C, D, for simplicity (and assume

there’s no list for “authorgroup”, so the

“_default” will be used).

The first two items match one and two items, respectively. They aren’t appropriate for a list of four items. The third item contains three items and a repeat, so that can be used for a list of four (or more) items.

The first %c is “A”. The second %c is

in a repeat, followed by another %c. There are three

elements left in the list at this point, so two will be used in the

repeat and the last one will follow it.

The result will be A, B, C, and D where the

word “and” was found by looking for the and key in

the mappings.

4.3.4. Letters

The letters group is used to identify the lexical order and grouping of letters.

1 | <letters>

| <l i="-1"/>

| <l i="0">Symbols</l>

| <l i="10">A</l>

5 | <l i="10">a</l>

| …

| <l i="20">B</l>

| <l i="20">b</l>

| …

10 | </letters>

All of the symbols with the same “i” value will be grouped together.

This mechanism dates from the days before XSLT supported language-specific collations. It is used in generated indexes, but perhaps it should simply be phased out.

4.4. Customizing a localization

For many users, the localizations provided are entirely sufficient. But if you want to change them, you have a few options.

4.4.1. Replacing entire localization files

If you want to replace an entire localization file (if, for example, you want to apply the same changes to a set of stylesheets), you can approach that as follows:

Copy the localization source files.

Update the ones you wish to change.

Compile them all with

src/main/xslt/modules/xform-locale.xslsaving the output in a new location.In your stylesheet, change the

$v:localization-base-urito point to the directory where the new locales reside. Those locale files will be used.

4.4.2. Overriding mappings, groups, etc.

If you only want to override a small number of localization

features, it may be simpler to do so directly in your stylesheet.

The varable $v:custom-localizations will be merged

with the default localizations before transformation begins.

Suppose, for example, that you wanted:

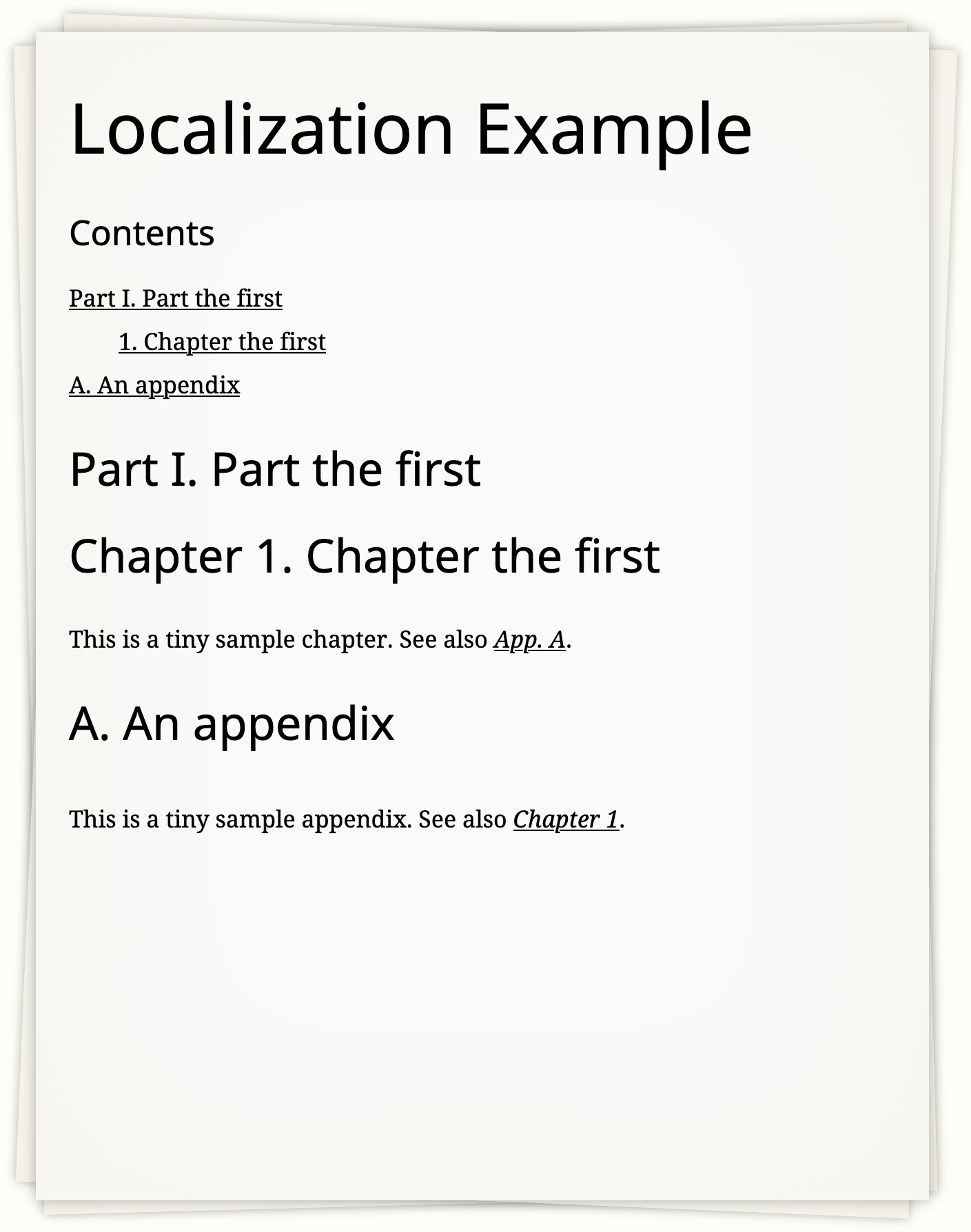

The table of contents title to simply be “Contents”,

To omit the word “Appendix” from the appendix title, and

To change the form of the cross reference to appendixes to read “App. A” instead of “Appendix A”.

The following customization would accomplish that:

1 |<xsl:variable name="v:custom-localizations">

| <locale xmlns="http://docbook.org/ns/docbook/l10n/source"

| language="en"

| english-language-name="English">

5 | <mappings>

| <gentext key="TableofContents">Contents</gentext>

| </mappings>

| <group name="title-numbered">

| <template name="appendix">%l%.%c</template>

10 | </group>

| <group name="xref-number">

| <template name="appendix">App. %l</template>

| </group>

| </locale>

15 |</xsl:variable>

Note that it defines (a portion of) a locale source file for the

language en. These changes only apply to that

locale.

This fragment replaces the mapping for

TableofContents and the templates for numbered

titles and numbered cross references.

To update multiple languages, put additional locale

elements in the variable as siblings.

Formatting our example document above now produces:

4.4.3. Changing the group

Sometimes, rather than change a template, you want to change

which group of templates is used. This is controlled by two variables:

$v:user-title-groups and

$v:user-xref-groups.

4.4.3.1. Changing the title group

The $v:user-title-groups element consists of a

list of title elements, each with an xpath

attribute, a group attribute, and an optional template

attribute.

Suppose the stylesheet is trying to generate a title for an

element. It considers each title element in turn. The

xpath expression is evaluated with the element as the

context item. If the effective boolean value of the expression is

true(), then that title is selected and templates from

the corresponding group are used.

If a template attribute is present, a template with

that name is used. Otherwise the local name of the element is used as

the template name.

By default, sections in a preface are not numbered. That’s because the default title groups include:

|<title xpath="self::db:section[ancestor::db:preface]"

| group="title-unnumbered"/>

If you add a title that matches sections in a preface to

$v:user-title-groups, it will take precedence.

For example:

|<title xpath="self::db:section"

| group="title-numbered"/>

Because all of the user groups are consulted first, it isn’t necessary to include the predicate that limits this title to sections in a preface (although it wouldn’t change the result if you did).

4.4.3.2. Changing the cross reference group

Cross references are processed just like titles, except that the

$v:user-xref-groups element consists of a

list of crossref elements.

The default for cross references to chapters and appendixes is

“xref-number-and-title”, so you get things like “Chapter

1. The Chapter Title”. In order to get a different presentation in the

localization example used in this chapter, the following localization

is used:

|<xsl:variable name="v:user-xref-groups" as="element()*">

| <crossref xpath="self::db:chapter|self::db:appendix"

| context="xref-number"/>

|</xsl:variable>

That’s why the cross reference to the first chapter is just “Chapter 1”.

4.5. Caveats

There’s currently little documentation to tell you which group or template to change. The names are supposed to be somewhat self explanatory (for speakers of English), but sometimes you just have to look in the stylesheet.

The formalgroup element is unique in DocBook in that

its label depends on what it contains. A formalgroup of

figure elements is itself a “Figure” where a

formalgroup of example elements is an

“Example”.

If you need to change it, you may have to create your own

template for the formalgroup element in the

m:headline mode. The default version is in

modules/titles.xsl.